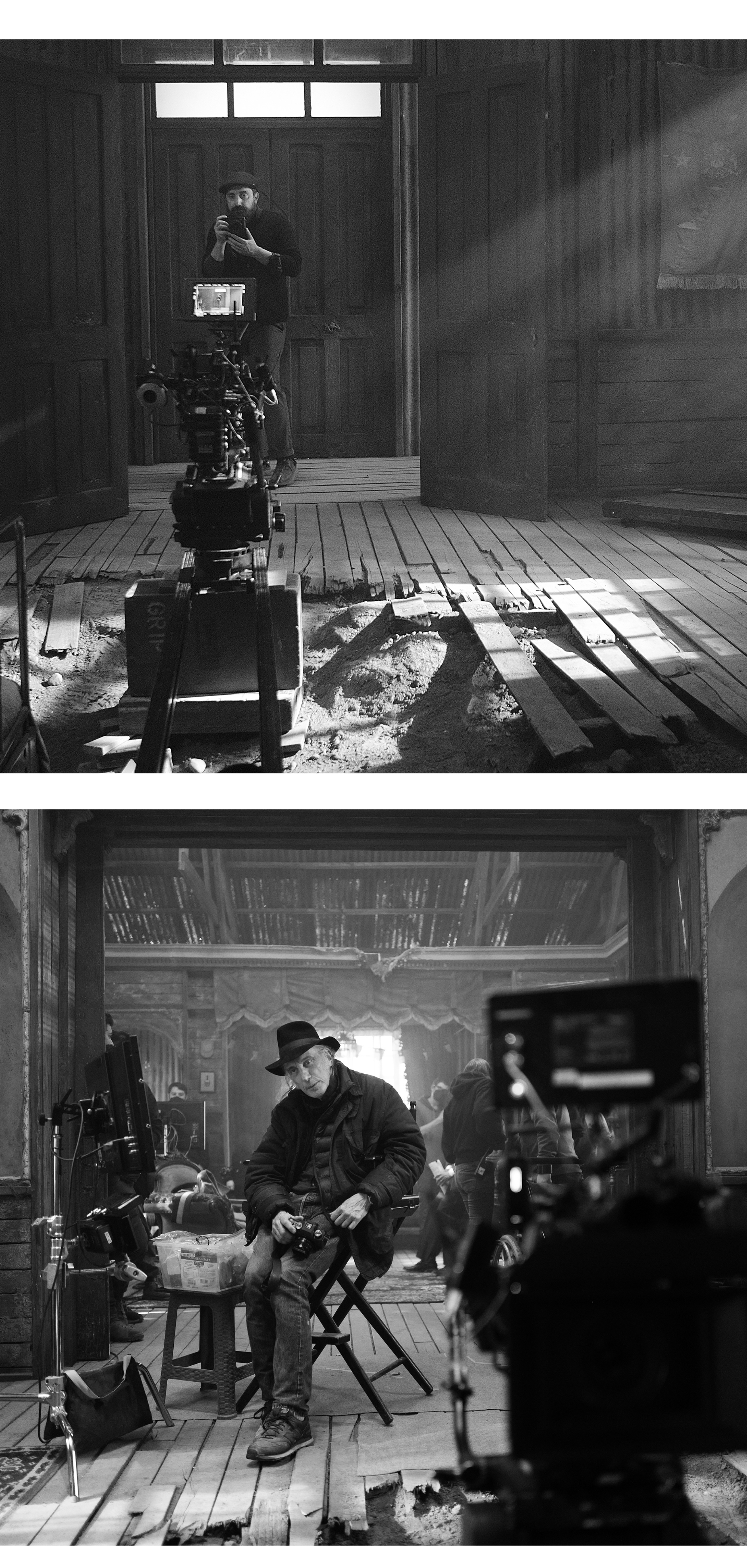

ED & JOE: A CINEMATOGRAPHER AND HIS COLORIST

Ed Lachman has nurtured a reputation for being an artist who expresses the themes of a film through its exposure, contrast, and color. Many who have worked with Ed, like director Todd Haynes, note that he is more of a painter than a cinematographer. (Haynes said in IndieWire: “He really is like a painter, more so than any other cinematographer I’ve ever met.”) If Ed Lachman is a painter, colorist Joe Gawler ensures he’s painting with the proper colors.

Joe and Ed met working on remastering Douglas Sirk films (Written on the Wind and All That Heaven Allows) for the Criterion Collection. Since then, they have graded three Todd

Approaching Every Story

with a Unique Lens

Ellie: Do you ever find it challenging that to make each project feel unique, or do they present themselves to you?

Ed: Every director’s story and every world offers an approach to the images. The characters, themes of the story, and the locations give me indications of how to approach it visually. That's what makes my job interesting. I try not to do the same thing over again but I don’t always know if what I’m doing will work or not. It may speak back to me in dailies or even after the film is edited. It’s the process with the script, director, and crew which affects how something ultimately looks or feels.

Joe: I would argue that you're probably a cinematographer, if not, the cinematographer, that other cinematographers look to and expect to see something different every time. You're not a one trick pony. You bring something fresh and unique every time. For my own work, I would say switching grading platforms, two years ago now, has reinvigorated me creatively to not just be pushing the same buttons every time. I have to think about it all over again, and the Baselight tools work in a different way. It's given me a fresh look on projects that I'm working on.

Ed: I can’t wait to see what you do with Maria [Maria, Larraín].

Joe: Ed, I was just thinking about the look of El Conde and how, I remember it being for Netflix. I started off with everything set up for HDR, thinking we were grading it for Netflix. I imagine the overall look, even on Netflix, is influenced by the fact that you and I graded the thing on projection.

Ed: Oh, that's a good point.

Joe: The contrast and the midtones, etc. I think it's also influenced by the fact that we spent two weeks on the film on projection. If we had done it on glass, it might have had a different contrast.

Ed: Right, I never thought of that.

Joe: You said, ‘get the monitor out of here. I don't want to look at that. I want to see projection.’ But we needed to grade on glass.

Ed: Is that better for you grade on glass or projection?

Joe: I can’t say which one is better. I just bet the film looks a little different because of the time we spent on projection versus on glass. I think the contrast sits in a different place, but that's just a guess.

Ed: Well, that’s an interesting thought

Shooting for Black & White

Ed: I also want to bring up the El Zone system where I could place the negative. I always joke that I felt like Ansel Adams shooting this black and white film. There were four factors that contributed to the look of the film. One - ARRI came up with a monochromatic LF sensor in two months for us. Two - I used Baltar lenses adapted for the LF camera. They were originally developed in 1938 used on films like Magnificent Ambers and Touch of Evil. This glass was designed for non-reflex rack-over cameras in the black and white period of Hollywood. The coatings were simpler, they had fewer elements, and the glass was hand polished. I also think that glass that has sat around for 75 years ages like wine due to exposure to the elements. Even though it’s an inert object, the way it’s stored, weather, exposure to UV light, all contribute to changes in the glass. Original Baltar glass was also manufactured with lead in it which is prohibited now. Three - I could use black and white filters for the contrast and texture in the scenes. Four - it was the first film to implement my EL Zone system which translated the digital image through analog interpretation and mapping of a shot to determine optimal range of exposure for the sensor, as I would do on film negative.

Joe: Yeah, I think that was part of what is drawing people to the work that you did, and we did together, is that contrast ratio, something that they're not used to seeing with digital images. Maintaining all that detail in the skies. This was our first time working on Baselight together, and it just gave us some new tools that Ed hadn't seen before. One of them was the base grades. That really helped roll off and maintain those highlights without having to pull so many keys which I know you were really impressed with that.

Ed: Like the windows.

Joe: Yes, just the ability to pull that detail back.

Ed: I held detail with the EL Zone, but obviously what you can do in Baselight could extend the exposure. An example would be the exposure in the windows and curtains. I was amazed how Baselight brought those curtains in.

Joe: Also, the texture operators.

Ed: Right.

Joe: So even with your lenses being vintage and softening everything as you build contrast, things can start to feel a little sharper. You have those sharper frequencies, and we were able to soften the sharper frequencies, which I'm doing on everything nowadays. It really gives a more pleasing image. In the past, we'd have to try to soften or blur the whole image and it just didn't look right. We were able to hit six different zones where we could roll out the sharpness from the sharpest bits to the broader frequencies. I think that gives it a nice overall texture.

Ed: Another point, in black and white while filming in different parts of the day, you can create consistencies as long as you are aware of the contrast and exposure and if it’s direct or indirect light. You’re not affected by color temperature in black and white as you would be in color film. It's all about your contrast.

Even with the blood we discovered – this was Pablo's idea – of shooting blood in different colors to find out which one worked best. Traditionally, we make it red because red has the deepest blacks, but we found by doing it in blue that it had a certain luminosity, that it was dark, but it still had a life to it.

If you’re interested in learning more about the look for El Conde, Ed himself recommends these two pieces, from Cinematography World and American Cinematographer.

Haynes projects (Wonderstruck, Dark Waters, and The Velvet Underground) and, in their most recent collaboration, Pablo Larraín’s El Conde, in which dictator Augusto Pinochet is reimagined as a vampire who has been alive for 250 years, the duo worked to control exposure’s contrast in black and white. For his work on El Conde, Ed has been nominated for an ASC Award, an Academy Award, and won the Silver Frog at CamerImage.

I purposefully took a back seat in this interview and let Ed and Joe talk. Given their longstanding collaboration, I decided it would be more interesting to let the conversation take them where it may. You will notice there are a few left turns, but hey, that’s life.

The "Ed Lachman Experience"

Joe: Congratulations, Ed. I don't think we've talked since the Oscar nomination.

Ed: Well. But I'm so glad that you're part of it. You're always part of it, you know.

Joe: I'm glad too, man. Just to get an Oscar nomination. Collaborating with you is pretty special. How many nominations is this for you now?

Ed: Three – Far From Heaven, Carol, and now El Conde.

Joe: Three times. That’s amazing.

Ed: Thank you, never a sure thing.

Joe: You and I have been working together for the last bunch of projects. What is key to that relationship?

Ed: You’re remarkable – how can I say it – you’re the best parts of a politician, able to mediate different ideas and sensibilities. You work in the most efficient way. Plus, you’re very open to ideas. You have the extraordinary ability to assimilate what people are working towards and present visual ideas to the cinematographer and the director to find a common ground. Not just sources for the film or on the digital file, but the personalities that are in that room.

Joe: I would agree and would add that, at least personally at this point in my career, it’s important to just have creative people that appreciate your approach. For example, when you and I are working together, I don’t anticipate any problems. I know I’m going to get the “Ed Lachman experience.” We’re going to make something beautiful. I am at this point in my life where I've got a lot of people that I continue to work with repeatedly because there's a level of comfort of an aesthetic. You know that we can collaborate and have a good experience at the same time. I imagine that's what any cinematographer is looking for. You'd love to have that person that you can go to on every show so that you have some confidence in what the experience is going to be.

Ed: Well, I had inherited a whole new crew in Chile [for El Conde, Larraín] which was a new experience for me, but I found them supportive and talented. Then on the last film I did for Pablo [Maria, Larraín], it was a large crew from Germany and Hungary and it was a similar situation. It’s always about finding the strengths and weaknesses of the people you’re working with and then maintaining positivity and working with their strengths, not their weakness.

Emulating Film via Digital

Ed: I do believe in the DI that we're getting better and better at a getting something that looks and feels like film to me.

Joe: The key is trying to get to that look through. It’s not just color. It’s not just grain. There's a bunch of other textures to get right without the audience feeling manipulated or seeing an Instagram filter. I've seen so many period films that are shot digitally and then a period look has been placed on top of it, at least to my eye. I'm so conscious of it.

Ed: In the digital world, it’s difficult to get that depth to an image because it’s on a fixed pixel plane, unlike film with its grain structure. Even though the difference between the three layers of film is microscopic, it affects the depth of the image. Now, people want to shoot wide open digitally because they think the out-of-focusness with the lens on the digital sensor creates the feeling of grain. But for me, it just feels like it's a digital device. It's not grain.

Joe: Yes.

Ed: Grain is much subtler than that. Whenever you're out of focus slightly in digital, it looks wrong. You can be out of focus in film and get away with it. It’s so hard to understand why, but I think it's because you don't need every part of the grain in focus to read the image.

Joe: You’ve brought that up when I'm adding grain in the DI. The grain is the very last thing we add, and any kind of softening you can get away with more easily, because at least the grain is sharp. Roman [Hankewycz] and I built this custom tool we call subtractive color so that we can increase saturation while reducing the brightness. As we've increased saturation or increased contrast, we notice the colors start to get zingy in an electric way. So, we built a tool that does the opposite. We’re getting deeper, richer, saturated colors, which I think you're going to like, Ed.

Ed: I look forward to trying to experiment with that on Maria.

Joe: For The Holdovers, I thought back to my experience from working at the lab fifteen years ago, sitting with the guys when they ran clear film through and printed it. And we'd watch it in the theater to see where the rollers were creating pressure marks and the chemical streaks and flicker. I have some of that.

Ed: Really?

Joe: Yeah, I just comped that into the image, so the image is subtly breathing; it's getting a little brighter, a little darker, and the color is shifting super subtly. And then I also tracked a scan film that that was slightly unstable. So, I added that throughout the entire show. But again, sometimes you watch a movie and they put all sorts of stuff on top of it and you feel that you're being tricked. I didn’t want that.

Ellie: Ed, do you think that in the future we will see a mix of film and digital?

Ed: It’s difficult to say. Four out of the five films nominated this year [for Best Cinematography at the ASC and The Academy Awards] were shot on film. It’s ironic that El Conde was the only film shot digitally even though I’m always the proponent of film. But honestly, the infrastructure for film is becoming increasingly difficult. I shot Maria on film in Budapest. The film had to be trucked in from London as they don't trust the X-rays at customs. So, I had to constantly create film orders how much film stock I would need three to four days in advance. Plus, it is getting harder to find loaders because it’s an entry-level position that requires preexisting knowledge on how to handle film, parts for film cameras are becoming less available, and experienced film technicians to work on cameras are retiring.

Joe: I used to be a loader.

Ed: Oh really?

Joe: Yeah, I didn’t last long though.

Ed: Well if you ever need job, I’ll hire you as my loader.