Outer Range Sound: Wyoming Landscapes and Supernatural Holes – POSTPERSPECTIVE

BY LOUIS GORDON

“The West is a place of wonder. It’s the kind of place where mysteries happen, and the land is a force.” That was the direction that Outer Range EP Brian Watkins gave to supervising sound editor Andrea Bella on how to approach sound design for the show.

Sounds mysterious, right? Well, that’s the thing with Outer Range, which can’t quite be pinned to any genre. It’s part Western, part murder mystery, part sci-fi.

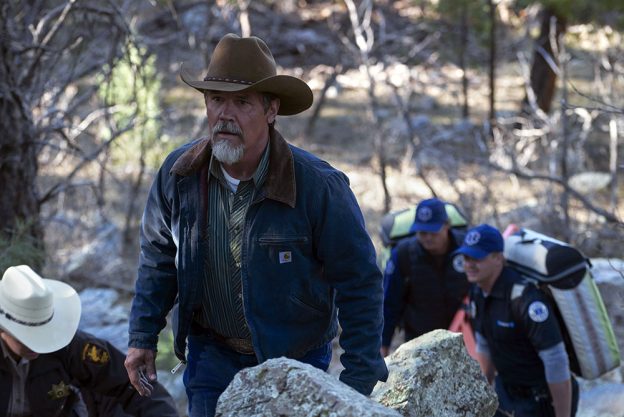

Royal Abbott (Josh Brolin), the patriarch of a modest cattle ranching family, has his hands full — from his oldest son Perry (Tom Pelphrey) bereaving his missing wife to his younger son Rhett’s (Lewis Pullman) passion for bull riding and late-night debauchery. Then add in an unwelcome hippie named Autumn camping on his land, which amazingly houses a bottomless hole in the ground with time-altering powers.

Outer Range manages a refreshingly original spirit. The vastness, oddity and intrigue of Wyoming and its inhabitants adds to the character. Bella, who worked out of Harbor in New York with the rest of the sound team, emphasized this point to me when we sat down to talk about crafting the mix, as it was one of her organizing principles: “We have the physical world, the beautiful landscapes of Wyoming, and we have the more internal world, inside the characters themselves. They also have many layers, and it’s where the characters live emotionally. Our approach for the sound design was to tackle each layer at a time.”

How do you begin to build those layers?

I watch the scene and then go to my sound libraries and listen to clips. With certain things like the [supernatural] hole in the ground, I’ll just throw stuff onto the tracks and run the scene. Does it sound good with this tone? I’ll shut off the dialogue and just watch the picture. Is this moving me in the way I want to be moved? Do I go with this metal, these bells or bass frequencies? Rhythm is also very important.

Sound designer Kevin Peters and I really got into details for each place and character. What the prairie is going to sound like, the Abbott house, the Abbott clock, every little element. The magpies… we decided you’d only hear this bird when we’re on this character

When it came to all these Wyoming landscapes, we really wanted to get the nature right and respect that environment. We did our research and made sure the birds, crickets and winds were accurate so that when we moved on to the more metaphysical world, like the hole, the two spaces interact, and the audience would feel that shift in environment.

What about designing that supernatural hole in the ground?

When we first started on it, we didn’t have picture (laughs). It was kind of fun trying to develop ideas with no image.

We tried some rocks, heavy earthquake-like sounds, but that wasn’t working at all. We trashed that idea and went with this concept of resonance and vibrations. The hole is a force acting on the characters. You know when you’re sitting and meditating, or you’re worried about something, you feel this buzzy energy in your mind? We tried that.

We broke it down into different tones and frequencies. We had high tones to represent the hole’s energy force when it’s “calling,” and the hole does call to people. We mixed the show in Dolby Atmos, and re-recording mixer Josh Burger was able to lift these sounds into the ceiling and move them around the air. It was wonderful.

Then we had what we called the low tones — the more metallic, darker sounds. We put down bass frequencies to feel the depth of the hole, but for us, these dark tones represented other moods. Larry [EP Lawrence Trilling] used to say, “OK, the hole is in sleeping hole mode” or “Now it’s an angry hole.” When the hole was angry, we’d take out more of those low tones, which are based on oil derricks. Basically, they represented natural resources being extracted. You’ll hear them groaning, rhythmically ratcheting up sometimes. It was also a way for us to symbolize counting time because the hole deals with time — the past, the future. It’s not linear. So the rhythmic groaning acted like a clock.

We had two more things we worked into the hole. The voice — those moaning sounds that were more soulful. Not to give away too many secrets, but we wanted to give a nod to the primordial and the primitive. There are buffalos, and they talk about mastodons in the show, about nature and how man has had his impact on it. Buffalos used to run that world, and then man came and took the power. So that voice is the cry of the buffalos.

At the hole, nature stops. Brian Watkins [the show’s creator] was very specific about that. So while we had all these wonderful prairie winds out in the forest, when we got to the hole, we used a very unnatural wind — electronic and phasey. We wanted the audience to feel that shift and know that nature is changing. There are also no crickets or birds there. Brian said to cut all that out. So the poor dialogue editors had to paint out as many crickets as they could because in the production sound, we did have crickets.

The rodeo scenes are a through-line for Lewis Pullman’s character, and the final rodeo in the series finale is a major moment. The sound design and mix of the entire sequence is almost symphonic. Can you break that down a little?

For the rodeos, we spoke to someone called Clay Lilley, who was the wrangler and the consultant on the show. He taught us all about rodeos. We bought these specific cowbells because we really wanted this to be authentic. You hear them when they’re lowering Rhett onto the bull, along with lots of leather and crunching and such. It’s sometimes a big ask to go and purchase special props like that, but it was quite fun.

The last rodeo was a very long sequence and had a lot of effects we cut in and then didn’t use. You’ll notice that there’s lots of crowd and audience in the first two rodeos. In the last one, the audience is much more absent. When he’s lowered into the bull, we went straight to music, which was awesome. The family is there rooting for him in the beginning, then slowly but surely, they aren’t there. He looks over and there are empty seats. I think that’s when he makes his own decision; he’s going to be his own man, he’s outta here.

We turned that audience-cheering background all the way down. Sometimes it’s much more emotional and impactful to have the absence of sound, you know? A moment doesn’t have to be sound effects. It could just be music or silence.

We tried to do that again later in the sequence when Cecilia has her breakdown outside the rodeo. The first time we mixed that was with the absence of sound. We dropped all the effects and dialogue out, so you just saw her moving her mouth. It was really interesting, but we had already used this technique, and sometimes when you use these techniques too often, they lose their charm. So we put everything back in and switched it up. That’s something you have to feel out while you’re in the mix because the mix is the first time where all these elements are coming together. We did a full round of Foley and effects, and we had the music…all these need to be put together and then, in context, in real time, you have to watch it through and decide what is really giving you the emotional support that you need for the scene.

It’s impressive to accomplish that under a tight schedule.

Oh yeah. The way this show ran, the schedule was insane. It was always shifting. We didn’t do things in sequential order. Poor Dan Edelstein, our ADR supervisor. When we started in September, he had to cue the ADR and loop group for all eight episodes at once, and the episodes were still being cut and moved around. He was constantly keeping up.

I had a huge team of dialogue editors. We had editors working one episode, others working another, meanwhile Kevin and I were hand-to-hand on effects from the beginning. Our original plan was for him to do one episode and I do another. Nope. We had to just get going and then merge, merge, merge! We would merge our sessions all the time, check things out, merge them back together, someone would go away and work on something, and we would merge it again.

It was so important that we got together early with Josh to come up with a plan for these handoffs. Josh and Kevin created a template for us that included Dolby’s Atmos renderer and reverb patches for the Foley. This allowed us to hear in the premix what was going to be put up on Atmos even though we were working in a 7.1 session. If we were doing a complicated scene in the mix and there were go-backs that needed to be done, Kevin or I could take that session and work on it with exactly what was done on that mix stage.

Were there other preferred tools or plugins you went to for this show?

Before I start any kind of gig, I talk to the re-recording mixer and ask for a template so I know what track arrangement they want. I’ll also ask about plugins and what we can use, so there’s agreement on it. Audio Ease Altiverb is great for Foley, and believe it or not, for sound design. Exponential Audio’s Stratus is something that Josh likes to use, and Kevin’s favorite toy is Envy, the modulation plugin by The Cargo Cult. He’s the Envy-meister, as we like to say.

As for me, I bought Timeless for this project, the delay plugin by FabFilter, which was awesome. I’ve also been using Trash, iZotope’s distortion module, a lot recently.

Did you use Trash on Outer Range?

Yes, I did.

You’re not gonna tell me what?

To quote Autumn from the show, “A girl has to have her secrets.” (laughs) I’ll just say this: Crunchy distortion isn’t just useful for weird stuff. You can put it on a normal sound just to punch it through the mix better. I worked on a doc once where we had these general-sounding, classic computer noises. I crunched it down because it sounded better. It’s not just compression. A little bit of distortion can also go a long way.

What was the most challenging aspect of working on this show?

I have two answers to that. On a supervising level, the schedule kept shifting, and that was a challenge because you can’t start staffing and crewing up when the dates are so fluid, especially at a time when New York was super-busy. We had to play musical chairs with people and get new editors because someone we wanted to work with wasn’t available to do the whole run of the show.

The dialogue and ADR editor was going to be one job, but because the schedule was condensed, we had to get someone strictly for ADR. Keeping track of every cut, which version each editor was working on, which version was going to our Foley house (Alchemy Post), which version is coming back, keeping it all on schedule and within budget — managing that and all the crew was a big challenge. (Our assistant sound editor, Ailin Gong, was a huge help with that. She made sure we wouldn’t literally fall into a hole.)

What was the biggest lesson learned on this show?

Not to be afraid. This show turned out much bigger than we thought it was going to be when we started. It was extremely exciting to work with such talented and creative people. It can be daunting, but you shouldn’t be afraid. Normally, I’m a very safe person. I would say, just jump, and trust that the universe will take care of you. Because if you do jump, you grow as a person.

Originally published in postPerspective.